This article was originally published on the web at communigate.co.uk/london/fuchsia/, however that website is defunct at July 2016. The copyright remains with the original author(s).

Fuchsias - Pests and Diseases

RED SPIDER MITE

Red spider mite (Tetranychus urticae) is perhaps one of the most difficult of pests, which affect many plants including fuchsia, to eradicate. Because they are so tiny they often go undetected until they are at epidemic proportions. They breed at an alarming rate, given the right temperature and humidity, and can soon become a serious problem, particularly if they are in a greenhouse. Numerous sprays can be used but the problem is that the mite inhabits the underside of the leaves, which makes it difficult to treat, and because of the rapid rate at which they breed they soon become immune to such sprays, even when they are alternated. There is a predatory mite, Phytoseiulus persimilis, which can be used to treat severe attacks but these mites also depend on the conditions of temperature and humidity being suitable. First signs of an attack can be discolouring, mottling or reddening of the leaves. On examination of these leaves you will find very fine webs where the mite gains some protection from sprays or predators, normally at the top of the plants. The mite thrives in hot and dry conditions, so it is particularly helpful in the greenhouse to keep a moist atmosphere by regularly misting the staging. At the first sign of red spider mite spray with a systemic insecticide and repeat at regular intervals.

Red spider mite (Tetranychus urticae) is perhaps one of the most difficult of pests, which affect many plants including fuchsia, to eradicate. Because they are so tiny they often go undetected until they are at epidemic proportions. They breed at an alarming rate, given the right temperature and humidity, and can soon become a serious problem, particularly if they are in a greenhouse. Numerous sprays can be used but the problem is that the mite inhabits the underside of the leaves, which makes it difficult to treat, and because of the rapid rate at which they breed they soon become immune to such sprays, even when they are alternated. There is a predatory mite, Phytoseiulus persimilis, which can be used to treat severe attacks but these mites also depend on the conditions of temperature and humidity being suitable. First signs of an attack can be discolouring, mottling or reddening of the leaves. On examination of these leaves you will find very fine webs where the mite gains some protection from sprays or predators, normally at the top of the plants. The mite thrives in hot and dry conditions, so it is particularly helpful in the greenhouse to keep a moist atmosphere by regularly misting the staging. At the first sign of red spider mite spray with a systemic insecticide and repeat at regular intervals.

FUCHSIA RUST - AN IMPROMPTU SURVEY By Nick Dobson

Fuchsia rust (Pucciniastrum epilobii) is probably the most serious disease to threaten the fuchsia. In the past, I have prevented rust by spraying my plants two or three times in the spring with Nimrod T. I have always found that the warm atmosphere in mid summer, combined with the early season spraying, has proved sufficient to ensure freedom from rust until well into the autumn when the cooler, damper atmosphere provides a good breeding environment for the disease. By the end of the season, rust can be controlled easily as afflicted foliage is removed when plants are cut back and defoliated in preparation for winter storage. Spraying the bare branches of the fuchsia (and the compost in which the plant is growing) with fungicide has always ensured that my plants end the season rust-free.

Fuchsia rust (Pucciniastrum epilobii) is probably the most serious disease to threaten the fuchsia. In the past, I have prevented rust by spraying my plants two or three times in the spring with Nimrod T. I have always found that the warm atmosphere in mid summer, combined with the early season spraying, has proved sufficient to ensure freedom from rust until well into the autumn when the cooler, damper atmosphere provides a good breeding environment for the disease. By the end of the season, rust can be controlled easily as afflicted foliage is removed when plants are cut back and defoliated in preparation for winter storage. Spraying the bare branches of the fuchsia (and the compost in which the plant is growing) with fungicide has always ensured that my plants end the season rust-free.

Fungal diseases arrived early due to the cool, damp so-called summer that we endured, and my early season preventative regime proved an inadequate buffer to the early onset of rust. Overnight, or so it seemed, the leaves of potential show bench specimens were covered in orange-brown spores. In most cases there was nothing for it but to cut the plants back, totally defoliated them, remove the old compost and spray them with fungicide in the hope that they will recover for next year. In the midst of all this carnage, a pattern emerged revealing a number of cultivars and species that appeared rust resistant and a number that proved particularly susceptible. In early August, a superb quarter standard of Monsieur Thibault was showing the first signs of rust. At the time I picked off all the afflicted foliage that I could find. When I returned to the plant one week later it was completely covered in rust spores on the upper side of the leaves as well as the lower. Six weeks after administering the radical “winter preparation” treatment (as described above), the plant is back in growth, covered in fresh rust-free foliage. Display and Shelford were the next to fall victim, followed by a lovely large hanging basket of Susan Green. The other rust-prone cultivars were: Phyllis, Harry Gray, Alison Ewart and Cambridge Louie. Of the species only Fuchsia magellanica and its variants showed any susceptibility to rust.

The outbreaks of rust were not isolated to particular areas of the garden, individual plants were stricken in a seemingly random pattern. Other cultivars, often growing next-door to real “rust buckets” proved either untouched by the disease or only succumbed after a long period of exposure (and then only suffered minor attacks). The rust-free species were F.glazioviana (grown next to a couple of plants dripping in rust), F.hatchbachii, F.procumbens and two encliandra types: F.thymifolia and F.minimiflora. Of the cultivars: Irene van Zoeren, Charlie Girl, Sylvia Barker, South Gate, Naughty Nicole, Beacon, Tom West, Border Queen, Lottie Hobby, and Checkerboard were all heavily exposed to rust but suffered no signs of attack whatsoever. Most remarkable of all was a large multi-plant specimen of Loulabell (judged “Best in Show” at the North Thames Fuchsia Jubilee), which, despite being sandwiched between two rust-ridden plants of Display, remained totally unblemished and smothered in flowers until late October. The rust-resistant qualities of triphylla hybrids are well documented, and none of my triphyllas suffered any rust at all. Cultivars such as Lye’s Unique, Marinka, Walz Jubelteen, Flash and Annabel did experience mild attacks of rust, but only late in the season.

It would be dangerous to draw firm conclusions from a study carried out in such an impromptu manner, but this survey does serve to highlight species and cultivars that have a high susceptibility to rust whilst suggesting others with a degree of resistance. I will continue to grow both Monsieur Thibault and Display despite their apparent weakness as regards rust, but in future they may require additional treatments of fungicide in early summer and I will be extra vigilant in searching for the first signs of disease. Clearly some of the species and cultivars have some resistance to rust. Over the years pest and disease resistance has not been a high priority for fuchsia breeders, but American growers have recently aimed to produce fuchsias resistant to the fuchsia gall mite (a major problem in California) by using some of the less common species in their breeding programs. Perhaps a range of fuchsias with rust resistance will eventually emerge. Sadly the parentage of most of our cultivars remains undocumented, so it is not possible to trace the original plants with disease resistance (modern DNA testing could overcome this problem, however), but even from my survey I have been able to note that three of my “rust resistant” cultivars (Loulabell, Irene van Zoeren and Border Queen) share a common ancestor in Leonora. This fact may be pure coincidence and Leonora might well be highly susceptible to rust, but proper research into the ancestry of disease resistant fuchsias could prove a boon for future growers, especially if we are to experience cool, damp summers that provide ideal conditions for disease.

FUCHSIA RUST - PREVENTION AND CURE By..N Dobson/Brian C Morrison

Generally speaking, the fuchsia is an easy plant to cultivate little troubled by disorders. Fuchsia rust (Pucciniastrum epilobii) is probably the most serious disease to threaten the fuchsia. This article seeks to provide a few tips for the prevention and/or control of the disease. At the outset, it must be said that conditions play an important role in the outbreak and severity of rust attacks. The rust spores require moist conditions to thrive, and in an average British Summer, the months of July and August (the middle of the fuchsia season) are normally dry and hot, greatly inhibiting the germination of rust spores. Rust infections are usually more likely to occur during Spring and Autumn when moisture levels are higher and temperatures cooler.

PREVENTION:- Whenever a large number of plants from one genus are gathered together in a confined area, potential breeding grounds for pests and disease are established. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that rust is most commonly imported into a collection from new stock from a nursery. Specialist nurseries take great care to maintain high levels of hygiene, but despite scrupulous efforts to supply clean plants, no nurseryman could guarantee that his fuchsias are 100 rust free. Consequently it is good practice to isolate new plants for at least two weeks before incorporating them into the main body of your collection. This practice will not only guard against rust infections, but will also limit the chances of introducing other fuchsia foes such as red spider and whitefly.

Weeds could possibly harbour rust spores, so remove all weeds from the environment in which your fuchsias are growing. This is particularly important in the case of rosebay willowherbs, a member of the same order of plants as the fuchsia (Onagracea), and prone to fuchsia rust too. Other plants of this order may play host to fuchsia rust, so, in the interests of fuchsia hygiene, it is probably best to avoid growing ornamentals such as godetias. The microscopic rust spores can be spread by the wind, by flying insects or on clothing. Therefore, when handling badly infected plants, wear overalls or other protective clothing that can be changed before you come into contact with healthy plants. Control of whitefly and other insects will diminish the threat of rust being spread from that source. In the greenhouse good air circulation will also help prevent rust.

CONTROL:- Vigilance is your most important weapon in preventing or controlling rust: “inspection not infection”. However, if infection does occur, the most efficient non-chemical control of the disease is to pick off all rust affected foliage. As mentioned above, great care should be taken when doing this in order to avoid spreading rust to other plants in your collection. Prevent rust spores from dropping onto the compost in which the plant is growing by positioning a paper collar around the base of the plant. Spores on the soil can easily be transferred back onto the foliage, thus causing reinfection and there is also a risk of the disease being taken up into the system of the plant via the roots. Infected leaves should be carefully disposed of by either burning or binning: never compost diseased material, as the risk of reinfection cannot be discounted. After all diseased foliage has been removed, it is good practice to scrape away and dispose of the loose compost at the top of the pot, thus expelling any spores that might have fallen onto the soil, and replace with fresh compost. In the case of plants with very severe rust infections, the only answer is to cut back the plant, removing all the green growth (as if preparing it for over wintering), replace the compost and spray the bare branches in the hope that the new growth will be rust free. As a last resort it may be necessary to dispose of a badly affected plant.

Edwin Goulding observed that in the war against pests and disease “no one method of control should be practiced repeatedly on its own” (Fuchsias: the complete guide, 1995). Resistance to specific chemicals can quickly be established by the rapidly reproducing pests and diseases. The chemicals available for rust control include myclobutanil, mancozeb and bupirimate with triforine, available in Systhane, Dithane 945 and Nimrod T respectively. Propiconazole, available in Tumbleblite, is also effective against rust, but can cause damage to fuchsia foliage and is therefore not suitable for use. Plants that have been subjected to rust attacks should be sprayed every ten days and in order to counteract the risk of the spores building up immunity, it is a good idea to use these products on a rotational basis. In addition, over use of one chemical can lead to a dangerous build up that substance in a plant (a process known as phototoxosity), so never exceed recommendations regarding the strength of the product in your spray and don’t be tempted to spray at closer intervals. Preventative spraying of healthy plants can also prove beneficial with any of the products mentioned above at three weekly intervals.

RESISTANT FUCHSIA'S:- Over the years pest and disease resistance has not been a high priority for fuchsia breeders, but American growers have recently achieved some success in producing cultivars resistant to the fuchsia gall mite (a major problem in California) by using some of the less common species in their breeding programs. Evidence from informal studies suggests that many of the fuchsia species as well as some of the cultivars have excellent resistance to rust even when heavily exposed to the disease (Dobson: “Fuchsia rust: an impromptu survey” BFS Spring Bulletin pp.23/24, 1999). A few breeders have already turned to species such as F.glazioviana and F.hatchbachii (two species with proven pest and disease resistant qualities) in order to introduce fresh blood into a gene pool weakened by years of inter-breeder due to the concentration on the magellanica-type fuchsias. Hopefully the establishment of FRI’s species and pre-1914 collections will help to provide hybridists with greater accessibility to a wider breeding stock. One of the consequences of this initiative could be the production of rust resistant fuchsias.

Rust is a serious problem for the fuchsia grower since infected plants can be badly weakened as spores restrict light from getting to the leaves thus reducing food production leading to stunted growth. The fact that rust is so highly contagious is probably its most dangerous aspect. However, good preventative measures combined with prompt controls as soon as the disease is identified, will help to reduce the rust problem and ensure healthy plants.

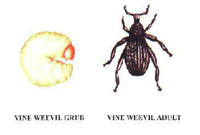

VINE WEEVIL By....Mick Allsop

The vine weevil (Otiorhynchus Sulcatus) has become a very serious pest in recent years attacking many plants, including fuchsia's. Nocturnal in habit the adult vine weevil does not fly but you may believe it does so by its agility in reaching almost impossible locations where it feeds on the leaves and lays its eggs. It appears that all adult vine weevils are female and are capable of laying around 500 eggs a week over a period of several months. Although the adult weevil does not do much damage, a few ragged notches cut from the leaves of host plants, it is the larval stage, the crescent shaped white maggot that is the real threat. Eggs are usually laid between August and September and the grubs, after hatching, set about devouring the root system and crown of of the plant, usually during the dormant season whilst the plants are stored over winter. The first you may know of their presence in when the growth of your plant seems a little slow and on checking the stem comes away from the soil. There are numerous remedies available, including nematodes (thread like worms), "Armillatox" and "Provado". It has also been reported that "Nippon" ant gel and wood lice powder attract and kill vine weevil although I have not tried this method myself. The most reliable way to combat this threat is to break the life cycle. Course grit on top of the soil acts as a deterrent to stop the adult laying eggs, but the most affective remedy, in my opinion, is to strip the plants, wash the root system, and repot in fresh compost before storing the plants at the end of the growing season. Any old compost should be discarded in the dustbin and not onto the garden.

The vine weevil (Otiorhynchus Sulcatus) has become a very serious pest in recent years attacking many plants, including fuchsia's. Nocturnal in habit the adult vine weevil does not fly but you may believe it does so by its agility in reaching almost impossible locations where it feeds on the leaves and lays its eggs. It appears that all adult vine weevils are female and are capable of laying around 500 eggs a week over a period of several months. Although the adult weevil does not do much damage, a few ragged notches cut from the leaves of host plants, it is the larval stage, the crescent shaped white maggot that is the real threat. Eggs are usually laid between August and September and the grubs, after hatching, set about devouring the root system and crown of of the plant, usually during the dormant season whilst the plants are stored over winter. The first you may know of their presence in when the growth of your plant seems a little slow and on checking the stem comes away from the soil. There are numerous remedies available, including nematodes (thread like worms), "Armillatox" and "Provado". It has also been reported that "Nippon" ant gel and wood lice powder attract and kill vine weevil although I have not tried this method myself. The most reliable way to combat this threat is to break the life cycle. Course grit on top of the soil acts as a deterrent to stop the adult laying eggs, but the most affective remedy, in my opinion, is to strip the plants, wash the root system, and repot in fresh compost before storing the plants at the end of the growing season. Any old compost should be discarded in the dustbin and not onto the garden.